All I Wanna Do

Hope you good people read this on your lunch break

It’s just after 12 on a Tuesday as I write and I am not in a bar facing a giant car wash. (Shout-out to Sheryl Crow’s best song, one that lives rent-free in my head, and not just because I had an instant crush on her when I first watched the video lo these many years ago.)

But I’m not a day-drinker. Lately, only an occasional night-drinker. I just drink less. I eat less sugar, too.

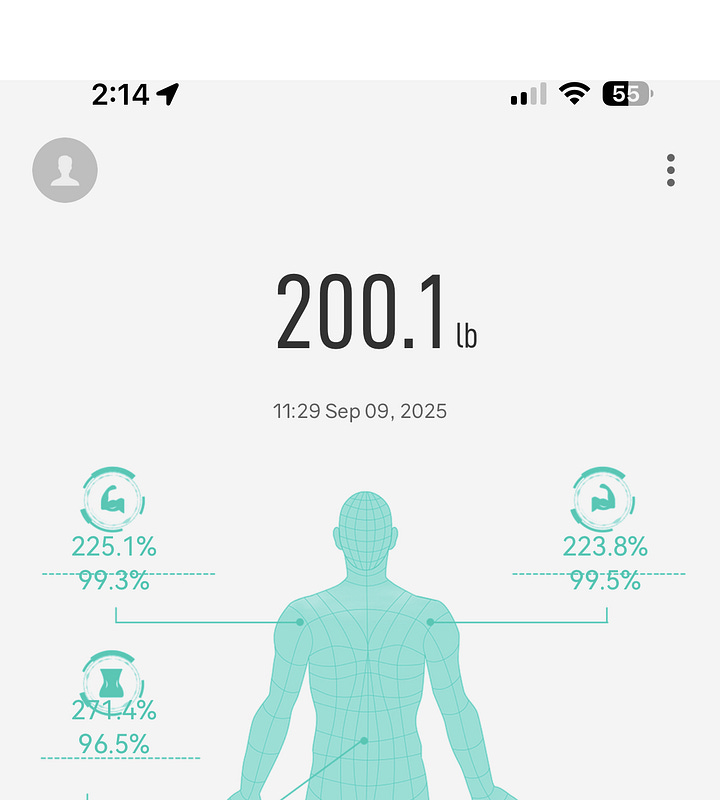

That’s one of the reasons I weigh 200 pounds now (at 6’0”), even as I’m staring down my 60s in 785 days. I’ve done it with Zepbound and copious amounts of usually carefully thought-out exercise, emphasizing strength more than cardio but still doing plenty of cardio (Don’t come at me about using a GLP-1. I’ve always struggled with my weight and this has been life-changing in the best way. I’m aware of the controversies that surround these meds and I simply don’t give a shit. Keep it to yourself).

I’m firmly in the camp of those physicians and fitness gurus who say the most valuable exercise you can do in old age is strength training.

Last year I went to the doctor around my 57th birthday for a physical and discovered my health was shit. I basically knew that, but it was even worse than I realized at the time. I weighed around 270 pounds and my blood pressure and cholesterol were terrible. I’d done exactly as I’m sure both my late parents knew I might after they died six months apart in 2023 and turned to my old-time favorites for coping with profound, debilitating depression—food, drink, and lassitude.

I’m not even sure I ate much more than normal, but I felt trapped in grief’s clouded amber like never before. I’d experienced plenty of loss since my teens (beginning in my teens) and understood how it works inside me, and still wasn’t prepared. Is anyone?

When I say there were times I couldn’t move, it’s not drama. I parked on the long end of our sofa (it has a nifty chaise longue-like extension that also stores bed clothes for guests like our older kids or my in-laws) and stared at the internet. I stared at the TV. I stared out the window. Luckily the view is pleasant—see above—as long as I remember to mow the lawn.

I felt like a disembodied pair of eyes mourning the ability to blink.

In my defense, a lifelong genetic issue with my hips also went critical in 2023. It was exacerbated by multiple 1,000-mile drives between Massachusetts, where I’ve lived for 13 years, and my home state of Tennessee. I’m close to being in the best shape of my life now, but the issue, hip dysplasia, can still pop up at random. Even yesterday, after I’d worked out and jogged a mile and a half with no issues. I got home with the groceries and stepped out of the car and felt momentarily like someone had driven a knife between my left hip socket and femur. I later stretched, breathed, relaxed, and it faded, but I was on my butt the rest of the night just for safety.

So I had a solid physical reason for being parked on the sofa so much, too, but in the end the main issue was a yawning chasm of grief-related depression that surpassed suicidal ideation and went right into feeling like a ghost.

My wife Dana understood and put up with some of my less desirable traits being even worse than usual. I am not sure I would’ve made it without her love and patience, and I am eternally grateful.

It was a latent, lingering sense of self-preservation and love for my remaining family that took me to the doctor for that physical. The results were the exact wake-up call I needed after watching how my parents suffered physically as they aged. Mom had compounded things with smoking, but she was from a long line of tough farm folk and still actively gardening well into her 70s. Dad came from similar stock. He only smoked till he was 30 but he was a chronic drinker. Not an alcoholic, exactly—I guess it depends on your definition of that, but I can only recall seeing him flat-out drunk one time, and Mom later said that was the only time she’d ever seen him that way too—but Bob loved him a beer or six at the end of the day and was still tossing back whiskey shots with me at dinner a month before he died.

In my father’s final week he was mostly asleep in palliative care, but even then he’d sometimes cry out in pain when nurses bathed him with a sponge and changed his bedding. It was horrific to see this man who had been an avatar of masculinity and physical strength to me as a little kid looking so fragile and broken. Not that he was responsible for his state, exactly. In Mom’s case, it was miraculous she lived as long as she did, given she’d always suffered from a long list of health problems despite being active, including severe anxiety (something I should’ve guessed given her Valium prescriptions but didn’t know for sure until she admitted it in her early 80s).

No, age gets us all in the end. I’ve got the genes for at least one nasty form of cancer (though it’s curable if caught early enough), and the Emperor of All Maladies loves to take advantage of the aging body by showing up just when you need it least—your senior years. I have never been under any illusions about living forever.

It’s just that I can’t shake the feeling I’ve got more to do. Even beyond knowing how adult children often still need their parents, especially kids like my youngest daughter and son, who are on the autism spectrum.

In the last year, as I’ve recovered my health, I’ve also recovered my love of singing. That process really began ten years ago, after a ten-plus year break from it, but buying a home in a quiet neighborhood, with a largeish lawn, meant I could truly dig into things, vocalize as loudly as needed, without worrying about pissing off the neighbors on the first two floors.

The slower part of the process was recovering caring about this, what you’re reading. About writing, the thing I knew I could do from the time I first cracked a book. That I wanted to do all my life but figured I didn’t have the patience for, until someone hired me to do it in 2005.

We all have some things we feel we are organically meant to do. I believe that. And as much as I love singing and have always been told I have a gift for it (I’m loud. That’s sort of the main thing a voice like mine does well, but I can carry a tune and do have a sense of musicality; I digress), it’s something I acquired.

I am a writer in my bones.

Yet in the last few years, I didn’t want to. First all I could think about was what I’ve spent many words discussing here—grief. You can only go on about that so much before you drive yourself and everyone around you kind of crazy. Then I realized some of the things that fueled my writing in the past were gone.

A lot of good writing advice says “write for one person you know, not everyone.” When it came to true crime, I was at first consciously then later subconsciously writing for my Mom. When it came to covering anything else, both parents were my subconscious audience. If I left something out, it was something I thought Dad might not care about, or Mom might find too upsetting. They were gone. So now what?

Good writing says I have to answer that question since I posed it and out of pure contrariness I’m tempted to say I don’t have an answer . But the answer is now I have to write for me. It’s hard to communicate just how strongly the on-the-job training I gained in the last 20 years says NO, BRO, THE AUDIENCE.

Of course audience matters. I wouldn’t bother with this if I didn’t want someone else to read it and hope that they somehow relate. But my experience as a professional writer has been entirely audience-driven, and in the last ten years that has begun to rankle, independent of anything happening in my personal life. Huge losses only compounded the feeling.

I didn’t bury the lede here, though I will gleefully embark on doing just that in the future if I fucking feel like it. In recovering as much of my health as I could, in finding joy in singing again, I had to figure out what would make me happy as a writer. It’s something that feels selfish even as I write it out. And corny. Because the lede is the actual title of this edition of this newsletter. All I wanna do is have some fun.

I leaned into writing for a living initially because yes, I was having fun in a way, keeping myself constantly engaged in what was happening in the world and getting positive feedback that encouraged me and negative feedback that often really helped me improve. I was getting paid for it, too! Whee!

Somehow, my parents’ deaths reset how I see this craft.

In the article “The Ultimate Rite of Passage - The Death of Your Parents,” Gail Marquardt writes that within “all the sadness and potential regret [from losing parents], there is an opportunity to retell ourselves the story of our lives. Our parents can’t make choices that affect us any longer. The circumstances of their lives will not factor into how we spend our days, time with our families, or moods. In a certain way, at the point when our parents die, a new life begins, one in which we have more autonomy than ever before. We can take control of the narrative.”

I guess that’s what I’ve come around to. I’m finally taking control of the narrative. And when it’s appropriate to the subject, I’m gonna have some fun.